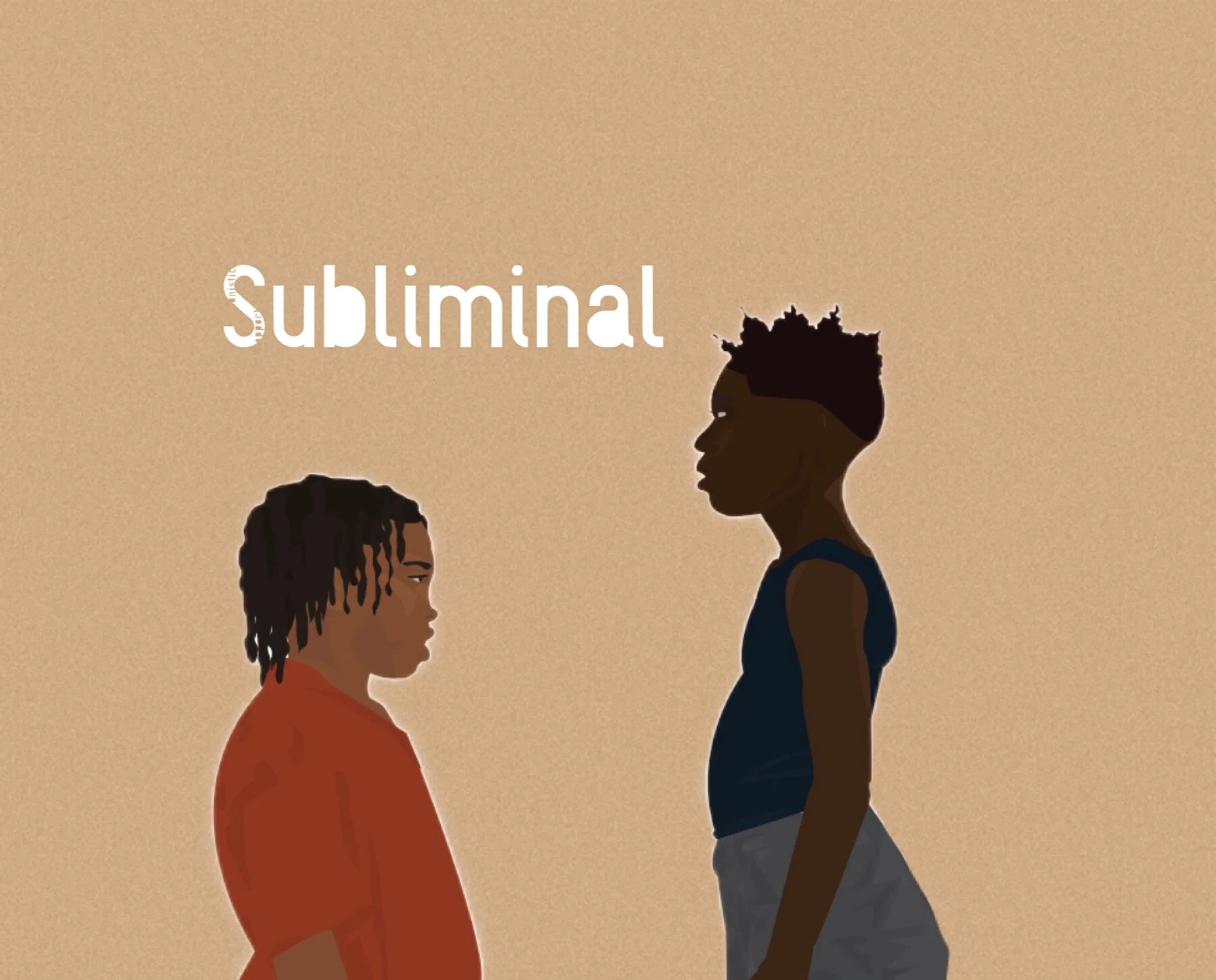

Subliminal

It was sunny at the intersection of Howard Road and Rue Antoinette. Little Black boys played in the yard. Their squeals and laughter were a delight for Mrs. Sanderson, who watched them play every day.

Off her porch, Mrs. Sanderson looked on as they ran round and round in circles. They panted but never tired as the sun made their sweat shiny on their foreheads. Little hands clasped together and made weapons of their index fingers. Their mouths were imitating bullets ricocheting off their bodies or firing into the air. Buoyant laughter bubbled out of chapped lips and through gapped teeth as they chased each other.

Freeze tag. Cowboys and Indians. Not all games had a name, but they played them anyway — harmless games at seven and nine years old — sad misconceptions at her age.

“I’m tired of playing this. Let’s play something else.”

It was Jamir who’d spoken. Chicken Legs, as Mrs. Sanderson called him. He was the taller, more slender one whose skin was dark like mahogany wood. A burnt-orange tank top clung to his scrawny body as he puffed his chest out, trying to catch his breath.

Ahmed was the smaller and chubbier one. She called him Gumbo. He had teeth that were too big for his face and a head full of dreadlocks. Sweat glowed on his fuzzy hairline. He replied, “You don’t never wanna play nothing. What do you want to do then?”

“We can play cops,” Jamir suggested, walking over to his cup on the front steps. He shooed away a fly off the rim and brought the cup to his lips. “Imma be the cop this time. You the bad guy.”

“Alright.” Ahmed nodded, waiting for his turn to take a sip. His momma didn’t let him go in and out of the house and waste her air. He relied on Jamir for his water and his popsicles.

“Go on over there, and then we’ll play,” Jamir said, always so bossy.

Mrs. Sanderson watched them from her rickety wicker chair. There in the shade, she was content as the breeze lifted her wispy, grey curls away from her face. As she continued to look out into the yard and across the street, she heard the ping of her oven. With hands creased like old leather, she grasped the armrests and lifted herself to fetch her treats. She moseyed into the small house that smelled of sandalwood and tobacco.

She liked to bake for the boys every now and again. They were the only two children who lived in the furthest cul de sac, their houses on either side of hers. They used to give her kisses and talk her up when they were younger, but those moments were rarer now. Gumbo was still sweet to her when Jamir wasn’t around, but he wanted to be cool when he was. She didn’t mind it; she remembered trying to impress the older kids too.

She hummed a tune as she arranged the lemon squares on a plate. Just as she brought them outside, she was startled by the commotion.

“Put your hands up, nigger! Where I can see them!” Jamir yelled, pointing his trigger finger at Ahmed.

Ahmed giggled with his hands in the air.

“Oh, you think this is funny?” Jamir charged at him, tackling him to the ground.

Once he’d knocked him to the ground, he quickly put him in a chokehold. Ahmed struggled against him, unable to laugh as freely now. They tousled on the ground, but Jamir restrained him again with his arms twisted behind his back. He pressed his knee into his lower back, keeping his wrists pinned. With his other hand, he pressed the heel of his hand against his cheek, pushing his face into the patchy grass.

“You’re under arrest, nigger.” Jamir continued to apply pressure with his knee.

“Screw you, pig! I ain’t do nothing!” Ahmed began to wriggle free as Jamir pretended to reach for his handcuffs.

Jamir let him go. Just as Ahmed got away, he poised his fingers and squinted one eye to practice his aim. Suddenly, he made an explosive, crackling sound to imitate the firing of the gun. Ahmed dramatically fell to the ground, motionless.

He rolled over soon enough and picked himself up. “My turn now.”

Again, they wrestled. Ahmed dug his knee into his spine as he arrested him with nothing but his imagined authority. Jamir played the part, gasping for breath beneath him and trying to free himself.

“Y’all stop all that roughhousing and come get your sweets.”

She hadn’t raised her voice, but it was biting as it reached their ears. The boys separated and shared a look before racing over.

Mrs. Sanderson was standing rigidly in her doorway. She watched the scene unfold with labored breaths, each one wringing her chest as she wondered what to say -- wondered if she should say anything at all. Her fingers were clenched around the plate of lemon squares, a deep sadness in the pit of her stomach as they climbed her porch.

She wanted to know where they’d learned to do a thing like that, but knew the answer already. Police encounters were rampant in their town. Drug busts and instigation frequently happened in the neighborhood. Little Black boys witnessed their role in the equation and replicated it. Some would grow up and fulfill it when it was no longer a game.

She wanted to scold them, tell them to stop being so ugly to each other. That police altercations should not end in death. Being shot by the cops was not the expectation. That it was nothing to make a game out of. She wanted to tell them about the friends she’d lost, the sons of her friends who were taken. The scathing reminders of the terrorized nights she stayed up when her own boy stayed out too late.

Instead, she just let them flock to her and take their treats, grateful they could still reach for them.